Culture Focus

Korean Traditional Recreation - 1

History of of Korean traditional recreation

Definition of traditional recreation

"play" which have been passed down by the people of those societies. In traditional recreation, "tradition" can be defined as "valuable social heritages that have been preserved and handed down from generation to generation", while "recreation" refers to all physical and mental activities outside those having to do with labor. It is characterized by voluntary participation and lack of purpose with regard to the everyday concerns of life. Therefore, recreation is associated with pleasure and excitement.In Korean, the noun nori (meaning "play")–which is the general term used to denote recreation–is derived from the root form of the verb nol-da ("to play") with an added noun marker. The verb "to play" has several nuances. Its meaning can be understood either passively as a time for relaxing when not working, or actively as activities which are intended for fun. Therefore, a more inclusive definition of recreation includes both relaxation and activities. Korean traditional recreation refers to activities that have been passed down through the generations in the country known as Korea.

Historical development of Korean traditional recreation

Forms of traditional recreation in Korea include competitions, entertainment, theater, acrobatics, and so forth. The history of Korean recreation is as old as the history of Korea and the Korean people, and can be traced back to ancient times. In this article, we will explore the historical development of traditional recreation in three different periods: ancient times to the Three Kingdoms period, the Goryeo period, and the Joseon period.(1) Ancient times to the Three Kingdoms period

The remote period before the establishment of the three kingdoms on the Korean peninsula was an era of primitive communities based on blood ties. As such, there were no class distinctions according to differences in social status or ruling power. The people of this age worked together and had the same religion. They formed a communal society, and we can assume that this was also reflected in the recreation of this time. Due to the lack of a hierarchy, all community members participated in recreation. This type of recreation is known as daedong ("great unity") recreation. Since recreation in this period was carried out as a way of predicting the success of the community's labor or of expressing gratitude for the fruits of that labor, we can see that recreation was closely tied to labor and faith.

As primitive societies evolved into chiefdoms, recreation began to assume diverse styles and forms. A chiefdom is a form of society centered round local communities under the rule of a chief. This era saw the full-blown adoption of agriculture, and the people's way of life became intimately connected with the farming calendar. Communities developed seasonal customs based on the farming calendar and the seasons, and recreation began to be performed around this cycle.

The "Eastern Barbarians" section in the Book of Wei in the Records of the Three Kingdoms from China records that the people of such kingdoms as Goguryeo, Buyeo and Yemaek held national festivals once or twice a year after completing important seasons on the agricultural calendar, during which they enjoyed various forms of recreation. Among these festivals were Yeonggo in Buyeo, Dongmaeng in Goguryeo, and Mucheon in Yemaek. The large-scale celestial god worship rituals held in the capitals of Buyeo and Goguryeo were called gukjungdaehoe, meaning "large assemblies of the state."

These festivals were a type of collective harvest ceremony. The participants believed that they would be granted everything they wished for by dancing for and appealing to that god. Everyone, regardless of their age or gender, joined in the festivities, drinking alcohol, sharing food, and singing and dancing through night and day. Traces of these festivals can be found in the gut (shamanistic ritual) performed in the modern-day dongsinje ("ritual for village gods"), in which the participants dance and appeal to the village god.

Silla and Baekje also held national festivals that included traditional recreation. Literature sources explain that Baekje festivals included diverse forms of recreation (japhui) such as dice games, ball throwing, and music and dancing. In Silla, diverse performing arts (baekhui) were more common, including mask dances, sword dances, the five talents, Cheoyongmu's dance, and Wonhyo's Muaemu dance. The excavation in 1975 of a dice called a juryeonggu from Wolji Pond in Gyeongju afforded us a precious glimpse of a particular aspect of the Silla nobility's recreational culture.

A juryeonggu was a 14-sided die with 6 square sides and 8 hexagonal sides. Unfortunately, the original artifact was lost in a fire during the restoration process, and only a replica remains today. Each face of the juryeonggu has a different forfeit written upon it, so we can see that the die was used during bouts of drinking to assign penalties to those who tossed the die. The penalties are as follows:

1. After drinking, dance without making any noise.

2. Let several people hit your nose.

3. Drink one glass of alcohol and laugh loudly.

4. Drink three glasses and take a step forward.

5. Refrain from laughing while other people tell jokes.

6. Sing by yourself and drink

7. Fold your arms and drink.

9. Pick someone to sing a song.

10. Sing a song called Wolgyeong.

11. Recite a poem.

12. Drink two drinks down in one.

13. Don't throw away something dirty given as a penalty.

14. Call yourself a goblin.

(2) The Goryeo Period

Recreation as an integral part of national festivals continued throughout the Three Kingdoms period and into the subsequent Goryeo period. As the national religion of Goryeo, Buddhism influenced the recreation of the time, as can be seen in the development of the Festival of the Eight Vows (Palgwanhoe) and the Lotus Lantern Festival (Yeondeunghoe). The Buddhist Festival of the Eight Vows was a religious ceremony that appeared during the Three Kingdoms period and became a national festival during the Goryeo period. All sorts of singing, dancing, and other performances were performed during this festival at the royal court and in other places. In particular, the location of the ritual was magnificently decorated with lamps burning incense on each side and on two stages called chaebung. The Lotus Lantern Festival is another Buddhist ceremony which ultimately became a national festival. During this festival, the palace was lit and decorated with many lanterns. Records show that alcohol and food were laid on, and music, dance and theater performed for the court officials. On the other hand, it was also a time to please the Buddha and the gods and to pray for the peace of the country and the royal family. These two events were the most important state ceremonies during the Goryeo period and were performed throughout history. The song and dance and other performance aspects of these rituals continued to develop as the festivals were passed down through the generations.

As King Seongjong of Goryeo (960-997 AD) accepted Confucian ideals, he ruled that recreational performances such as singing and dancing were vulgar and abolished them. However, in national festivals like the Festival of the Eight Vows and the Lotus Lantern Festival, which had been passed down since the time of Silla, singing, dancing, and other kinds of performances were still performed on decorated stages called chaebung. This type of recreation continued until the Joseon period.

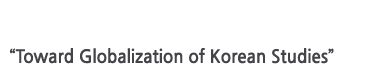

In the second half of the fourteenth century, the various types of recreation performed on the chaebung began to be called sandae japgeuk (various types of plays with chaebung in the background). With the installation of a stage, distinctions arose between people who were directly involved in the production and those who simply watched. Therefore, after the introduction of the sandae japgeuk, the king and nobles participated in the Festival of the Eight Vows, but only as spectators of those who performed the sandae nori on stage.

narye, which originated in China, became popular. During this rite, people wearing masks used props and chanted charms to chase away evil spirits. Over time, the narye rite replaced the more traditional large assembly of the state (gukjungdaehoe) of the Festival of the Eight Vows. The narye rite also changed over time, eventually becoming more of a theatrical performance than a ritual for repelling evil spirits. Professional actors called uin or changu appeared to entertain the crowd. Thus, in the midfourteenth century, the narye rite was divided into two distinct parts: guna, which contained the religious functions, and nahui, which included performing arts such as acrobatics and mask plays.

(3) The Joseon Period

With the transition to the Joseon period, the national festivals and the Buddhist ceremonies of the Festival of the Eight Vows and the Lotus Lantern Festival were abolished under the state policy of sungyueokbul, whereby Confucianism was promoted at the expense of Buddhism. However, the narye rite originating from China and the sandae nori continued to be transmitted to subsequent generations and became even more prevalent. During the reign of King Gwanghaegun (1608–1623), government offices were established to oversee sandae nori and narye events. In particular, the sandae nori was performed when envoys from China visited the court.

Sandae nori eventually became valued for its entertaining aspects even outside of large national events like the Festival of the Eight Vows or the Lotus Lantern Festival, and it increasingly became the exclusive property of the ruling class. When needed in the palace, a high stand would be erected and professional performers chosen from among the servants in the palace who lived outside the walls of Seoul would be ordered to perform for the entertainment of the king and his vassals.

As can be seen, recreation changed during this period from the style of large assemblies of the state, in which all members of society participated, to a style focused on watching entertainers perform, as with the sandae nori. As a result of this change, the participants in recreation became separated into two groups: professional performers and spectators from the royal class. As it was difficult for commoners to participate in recreation even as spectators, the classes became separated even in the world of recreation.

Sandae nori fell out of favor after the reign of King Injo (1623–1649) of the Joseon dynasty. Subsequently, sandae nori and other types of recreation moved from the royal court into the private domain. The style of recreation became more individualized and smaller in scale, and different styles of recreation gradually came to be associated with particular social classes. It was illegal for commoners to take part in recreations devised exclusively for the aristocracy. The styles of recreation reserved solely for the ruling class of this time included gyeokgu, tuho, and ssangnyuk (doublesix game).

Gyeokgu is a game played on horseback. The players use a long stick to hit a ball into their opponents' goal. Unsurprisingly, it was difficult for commoners to play this game because it required horses and a large area, so it became the preserve of the ruling class. There are many records in the Annals of the Joseon Dynasty about the kings of Joseon playing gyeokgu.

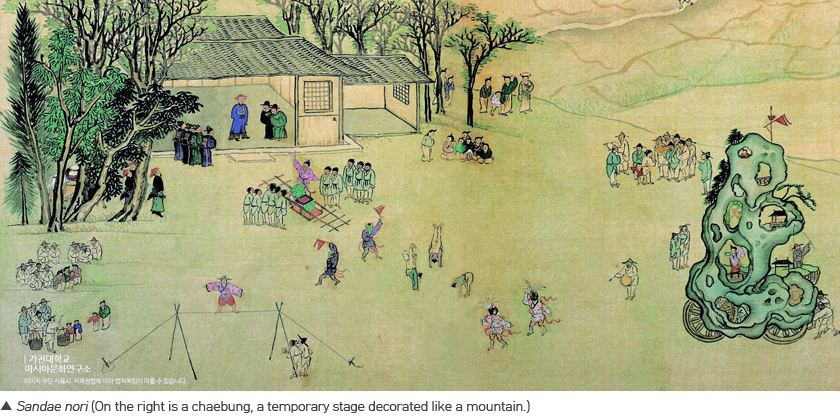

Tuho was a game in which the players attempt to throw red or blue arrows into some kind of bottle or vase. The player who succeeds in throwing the most arrows into the bottle wins. Records of tuho can also be found in the Annals of the JoseonDynasty, so we can guess that this type of recreation was also likely played in the royal court.

"The ancient kings would play gyeokgu in the winter, tuho in the summer, and archery in the spring and fall. Now that it is winter, it is time for gyeokgu. I will play gyeokgu with the crown prince and several vassals."-Annals of King Sejong, Book 44, 13thyear, 11th month, Imsinjo.

gyeokgu nearly disappeared during the reign of King Hyojong (1649–1659). In its place, a similar game played without horses and called jangchigi (Korean field hockey) was widely adopted by the common people. As for tuho, it survived because the yangban (ruling class) believed it to be a means of disciplining the mind.

With the transition to the Joseon period, the national festivals and the Buddhist ceremonies of the Festival of the Eight Vows and the Lotus Lantern Festival were abolished under the state policy of sungyueokbul, whereby Confucianism was promoted at the expense of Buddhism. However, the narye rite originating from China and the sandae nori continued to be transmitted to subsequent generations and became even more prevalent. During the reign of King Gwanghaegun (1608–1623), government offices were established to oversee sandae nori and narye events. In particular, the sandae nori was performed when envoys from China visited the court.

Sandae nori eventually became valued for its entertaining aspects even outside of large national events like the Festival of the Eight Vows or the Lotus Lantern Festival, and it increasingly became the exclusive property of the ruling class. When needed in the palace, a high stand would be erected and professional performers chosen from among the servants in the palace who lived outside the walls of Seoul would be ordered to perform for the entertainment of the king and his vassals.

As can be seen, recreation changed during this period from the style of large assemblies of the state, in which all members of society participated, to a style focused on watching entertainers perform, as with the sandae nori. As a result of this change, the participants in recreation became separated into two groups: professional performers and spectators from the royal class. As it was difficult for commoners to participate in recreation even as spectators, the classes became separated even in the world of recreation.

Sandae nori fell out of favor after the reign of King Injo (1623–1649) of the Joseon dynasty. Subsequently, sandae nori and other types of recreation moved from the royal court into the private domain. The style of recreation became more individualized and smaller in scale, and different styles of recreation gradually came to be associated with particular social classes. It was illegal for commoners to take part in recreations devised exclusively for the aristocracy. The styles of recreation reserved solely for the ruling class of this time included gyeokgu, tuho, and ssangnyuk (doublesix game).

Gyeokgu is a game played on horseback. The players use a long stick to hit a ball into their opponents' goal. Unsurprisingly, it was difficult for commoners to play this game because it required horses and a large area, so it became the preserve of the ruling class. There are many records in the Annals of the Joseon Dynasty about the kings of Joseon playing gyeokgu.

Tuho was a game in which the players attempt to throw red or blue arrows into some kind of bottle or vase. The player who succeeds in throwing the most arrows into the bottle wins. Records of tuho can also be found in the Annals of the JoseonDynasty, so we can guess that this type of recreation was also likely played in the royal court.

"The ancient kings would play gyeokgu in the winter, tuho in the summer, and archery in the spring and fall. Now that it is winter, it is time for gyeokgu. I will play gyeokgu with the crown prince and several vassals."-Annals of King Sejong, Book 44, 13thyear, 11th month, Imsinjo.

gyeokgu nearly disappeared during the reign of King Hyojong (1649–1659). In its place, a similar game played without horses and called jangchigi (Korean field hockey) was widely adopted by the common people. As for tuho, it survived because the yangban (ruling class) believed it to be a means of disciplining the mind.

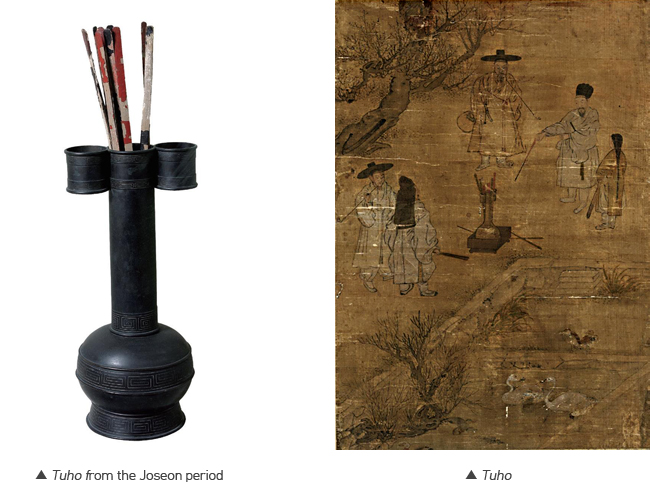

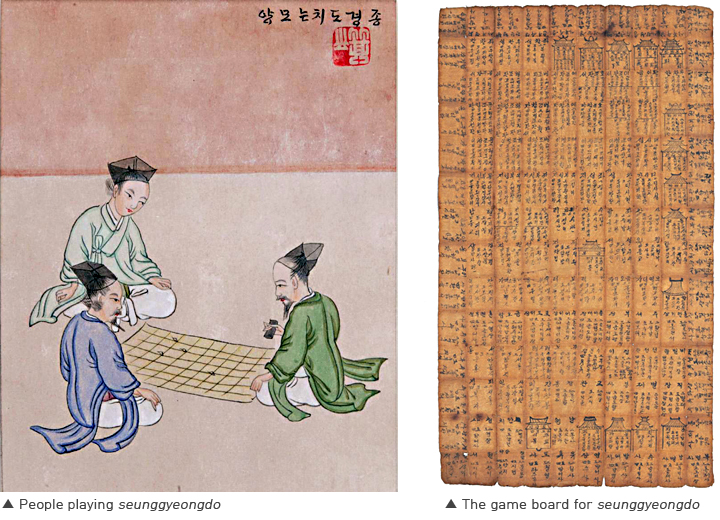

Other games include seunggyeongdo, in which the winners are chosen by throwing dice. It is a kind of board game in which units of the bureaucratic structure and names of government officials are written on a piece of paper. The players toss traditional dice or Korean dice called yunmok (sticks used as dice), and the player who rises to the highest government office first wins the game. Seunggyeongdo is also sometimes called jonggyeongdo or jongjeongdo, meaning a "chart that shows the life of government officials." The players take turns moving their pieces forward according to the number they roll on the dice or the long, five-sided yunmok. The first person to reach the final position, called bongjoha (a special title granted to retired officials), is the winner.

Seunggyeongdo was a traditional game usually played by the children of the yangban. The children of aristocrats used it as a method of learning the different structures of the Joseon dynasty's bureaucracy. This is because, even though the number of government officials in the central and regional offices did not exceed 3,800, the titles and relationships between each office were very complicated. The game could be played throughout the year, but it was more popular during the first month of the year because many believed it would predict one's fortune for that year.

The game board was the most important piece of equipment and was usually about 80 centimeters wide and 120 centimeters long. A grid was drawn on the board like the game of go, and the title of a government position, along with instructions on where to go next, were written inside each square. The number of squares varied from 80 to 300. The number of squares and the methods of writing the government positions also varied, but the outside columns and rows typically included the local posts of the governor, commander, investigator, and county magistrate, while the inside portion of the board included the different levels of the central government.

The game was typically played as follows. First, each player would choose one of several possible starting points, such as civil service (mungwa), military service (mugwa), hermetic scholar appointed by the king (eunil), or child of a current official who can receive a government post without taking the civil service examination (namhaeng).

After each player had chosen their starting point, they would take turns throwing the dice and moving their pieces according to the numbers on the dice. The player who reached the highest level first won the game. The highest level in the civil service track was the chief state councilor, while the highest level in the military track was the supreme field commander.

Game play was advanced as players could assume important government positions in the game; some positions might give a player the ability to dismiss or execute another player. For example, if a player became an official at the Office of Special Advisors (hongmungwan), they could dismiss a player who had gained a higher position on the board, and that player had to remove their piece. However, the dismissed player now had the opportunity to throw the dice. If they rolled a predetermined number, they would be safe and could return to their original place on the board, and they could also dismiss the official at the Office of Special Advisors who had kicked them out.

In-game penalties included dismissal, exile, and execution. A player who had been dismissed or exiled could return to play later on, whereas execution eliminated the player from the game immediately and permanently.

Seunggyeongdo was a traditional game usually played by the children of the yangban. The children of aristocrats used it as a method of learning the different structures of the Joseon dynasty's bureaucracy. This is because, even though the number of government officials in the central and regional offices did not exceed 3,800, the titles and relationships between each office were very complicated. The game could be played throughout the year, but it was more popular during the first month of the year because many believed it would predict one's fortune for that year.

The game board was the most important piece of equipment and was usually about 80 centimeters wide and 120 centimeters long. A grid was drawn on the board like the game of go, and the title of a government position, along with instructions on where to go next, were written inside each square. The number of squares varied from 80 to 300. The number of squares and the methods of writing the government positions also varied, but the outside columns and rows typically included the local posts of the governor, commander, investigator, and county magistrate, while the inside portion of the board included the different levels of the central government.

The game was typically played as follows. First, each player would choose one of several possible starting points, such as civil service (mungwa), military service (mugwa), hermetic scholar appointed by the king (eunil), or child of a current official who can receive a government post without taking the civil service examination (namhaeng).

After each player had chosen their starting point, they would take turns throwing the dice and moving their pieces according to the numbers on the dice. The player who reached the highest level first won the game. The highest level in the civil service track was the chief state councilor, while the highest level in the military track was the supreme field commander.

Game play was advanced as players could assume important government positions in the game; some positions might give a player the ability to dismiss or execute another player. For example, if a player became an official at the Office of Special Advisors (hongmungwan), they could dismiss a player who had gained a higher position on the board, and that player had to remove their piece. However, the dismissed player now had the opportunity to throw the dice. If they rolled a predetermined number, they would be safe and could return to their original place on the board, and they could also dismiss the official at the Office of Special Advisors who had kicked them out.

In-game penalties included dismissal, exile, and execution. A player who had been dismissed or exiled could return to play later on, whereas execution eliminated the player from the game immediately and permanently.

Recreation during the Joseon period is characterized not only by separation according to social status, but also by separation between ritual and recreation. While many rituals included aspects of recreation, many were transformed to exclude recreation due to the dominant Confucian ideology. The dongsinje (ritual for village gods) is an example of this. This local festival was transformed into a ceremony in which prayers were read.

The meaning of traditional recreation also changed with the social stratification of recreation. Through the period when the large assemblies of the state (gukjungdaehoe) were enjoyed by all without discrimination, there were no other types of folk recreation among the common folk. This is because the customs of the people were the customs of the whole country. People enjoyed recreation together without social discrimination in community recreation or large assemblies of the state.

With the rise in popularity of sandae nori, the people who actually participated in recreation were separated, and a new relationship between people who participated in recreation and people who merely watched it arose. Because the traditions of commoners, yangban (ruling class), and officials diverged in opposing directions, the duality of traditional recreation has persisted into the modern age. From this time, "folk recreation" took on a different meaning–traditional recreation enjoyed by the non-ruling class. However, when discussed today, traditional recreation includes both the traditional recreation of the common people and the recreation of the yangban class and the ruling class.

The meaning of traditional recreation also changed with the social stratification of recreation. Through the period when the large assemblies of the state (gukjungdaehoe) were enjoyed by all without discrimination, there were no other types of folk recreation among the common folk. This is because the customs of the people were the customs of the whole country. People enjoyed recreation together without social discrimination in community recreation or large assemblies of the state.

With the rise in popularity of sandae nori, the people who actually participated in recreation were separated, and a new relationship between people who participated in recreation and people who merely watched it arose. Because the traditions of commoners, yangban (ruling class), and officials diverged in opposing directions, the duality of traditional recreation has persisted into the modern age. From this time, "folk recreation" took on a different meaning–traditional recreation enjoyed by the non-ruling class. However, when discussed today, traditional recreation includes both the traditional recreation of the common people and the recreation of the yangban class and the ruling class.

Infokorea 2020

Infokorea is Korea introduced a magazine designed for readers with an interest in Korea and other foreign producers textbooks and teachers. Infokorea is the author of textbooks or foreign editors and reference to textbooks, Korea provides the latest information that teachers can use in teaching resources. Infokorea also provides cultural, social and historical topics featured in Korea. The theme of the 2020 issue was overview of Korean Traditional Recreation.

Infokorea is Korea introduced a magazine designed for readers with an interest in Korea and other foreign producers textbooks and teachers. Infokorea is the author of textbooks or foreign editors and reference to textbooks, Korea provides the latest information that teachers can use in teaching resources. Infokorea also provides cultural, social and historical topics featured in Korea. The theme of the 2020 issue was overview of Korean Traditional Recreation.