Culture Focus

Life in the Joseon Royal Palace - 1

The Sleeping and Rising of Kings

According to Sejong sillok (the chronicles of King Sejong), King Sejong used to wake up around three o'clock every morning for a dawn assembly with government officials. According to the literature, King Sejong was scrupulous in observing this routine, called "the four times of the king": the morning assembly upon arising; the audience with visiting officials later in the morning; a Confucian lecture in the afternoon to review the royal court's rules and regulations; and private life at night, a time to train the body and the mind.

The same daily routine was in place for all the kings of the Joseon Dynasty. The four times of the king were also deeply interwoven with the organization of the space in the royal palace. During the first three portions of his day—that is, dawn, late morning, and afternoon—a king stayed either in the jeongjeon (royal audience hall) or the pyeonjeon (king's office). At night, he stayed either in his bedroom or in the jungjeon (the central hall, which was also the queen's hall) or in one of the royal concubines' rooms in the back of the palace.

Officially, the king went to sleep after the city bells rang out twenty-eight times to signal the beginning of the nighttime curfew. This signal, called ingyeong, began at ten o'clock every night at the Borugak Pavilion, the site where the court's water clock stood. From there it continued to Jongnu, the bell tower; Namdaemun Gate, the southernmost entrance to the capital city; and then Dongdaemun Gate, the city's eastern entrance. When ingyeong sounded, the four gates to the city closed. The action of signaling the night curfew by ringing the bells was called injeong, and it symbolized the twenty-eight constellations that were believed to be the protectors of the sky. Injeong had a symbolic meaning: a wish for peace during the night. After injeong, patrolmen patrolled the town, making warning sounds with wooden clappers.

Paru was a sound that signaled the lifting of the night curfew. For paru, bells were rung thirty-three times, ending at four o'clock in the morning. Like ingyeong, paru also began at Borugak Pavilion and continued to Namdaemun Gate and Dongdaemun Gate. Originally, injeong involved ringing a bell and paru involved beating drums. It was thought that the sounds must be different as night and day had different characters, with night being yin (negative energy) and day being yang (positive energy). Joseon-era Koreans believed that iron bells were yin, which symbolized night and sleep, while drums made of wood and leather were yang, which symbolized day and activities. So it was believed that injeong should be a bell sound for comfortable sleep in the night and paru should be a drum sound to wake people up in the morning with enough energy.

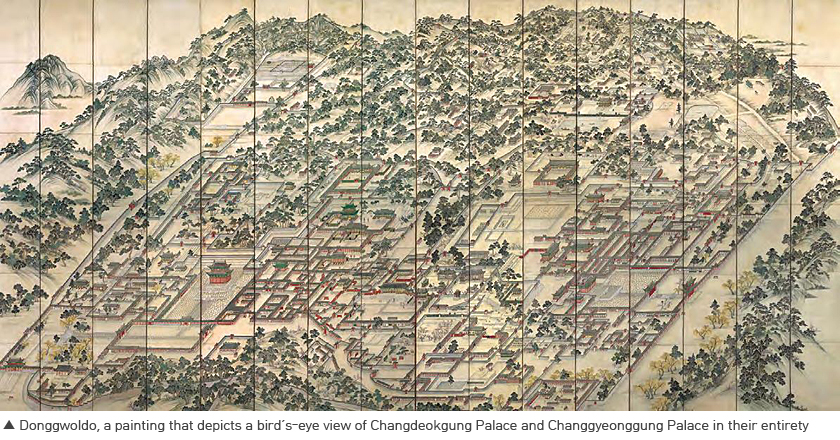

As the king had to wake up at paru, a water clock in Borugak Pavilion was installed near the king's bedroom or the rooms of the queen and concubines, to tell the time. In Gyeongbokgung Palace (the royal palace of the Joseon Dynasty), a water clock tower was located on the west side of Gangnyeongjeon Hall, the king's living quarters. During the reign of King Sejong, Jagyeongnu, an automatic water clock was invented and installed in Borugak Pavilion in the south side of Gyeonghoeru Pavilion. Special soldiers called jeonnugun (soldiers who announce the time) were stationed at every corner of the palaces and they would call out the time according to the water clock towers.

Since the chambers where the kings slept had ondol heating systems—which meant the heat came up through the floors—kings slept not on beds but on thin mattresses placed on the floor, with pillows and blankets as well. There were staff and facilities nearby to provide whatever he needed. Jimil-sanggung (palace matrons assigned to the king's bedroom) stayed just outside on standby overnight. Daejeon-chabi (palace custodians) who were in charge of kings' meals, the water he needed for washing, and the clothes he needed to put on at dawn, always stayed near the king's bedroom.

When the king woke up after paru, jimil-sanggung made bed, cooks at suragan (royal kitchen) prepared foods, and palace maids brought water for king's washing. Hwan-gwan (palace eunuch) also woke up to wait for king's orders.

Early morning was a time for the kings to get ready to display the dignity of the highest-ranking man in the country. During the night, the king slept like any other human being, but in the process of his early morning routine—having breakfast, getting dressed, and putting on a hat with assistance from servants—the king restored his dignity and authority again.

The bedroom for kings of the Joseon Dynasty was called jimil. Jimil referred to a space that was the most important and restricted in the entire palace, from which not one word spoken in it could leak outside. In such a space, the king stayed not with his queen but with maids of the court. The court maids who were assigned to work at jimil were called jimil-gungnyeo (court maids working at jimil).

The same daily routine was in place for all the kings of the Joseon Dynasty. The four times of the king were also deeply interwoven with the organization of the space in the royal palace. During the first three portions of his day—that is, dawn, late morning, and afternoon—a king stayed either in the jeongjeon (royal audience hall) or the pyeonjeon (king's office). At night, he stayed either in his bedroom or in the jungjeon (the central hall, which was also the queen's hall) or in one of the royal concubines' rooms in the back of the palace.

Officially, the king went to sleep after the city bells rang out twenty-eight times to signal the beginning of the nighttime curfew. This signal, called ingyeong, began at ten o'clock every night at the Borugak Pavilion, the site where the court's water clock stood. From there it continued to Jongnu, the bell tower; Namdaemun Gate, the southernmost entrance to the capital city; and then Dongdaemun Gate, the city's eastern entrance. When ingyeong sounded, the four gates to the city closed. The action of signaling the night curfew by ringing the bells was called injeong, and it symbolized the twenty-eight constellations that were believed to be the protectors of the sky. Injeong had a symbolic meaning: a wish for peace during the night. After injeong, patrolmen patrolled the town, making warning sounds with wooden clappers.

Paru was a sound that signaled the lifting of the night curfew. For paru, bells were rung thirty-three times, ending at four o'clock in the morning. Like ingyeong, paru also began at Borugak Pavilion and continued to Namdaemun Gate and Dongdaemun Gate. Originally, injeong involved ringing a bell and paru involved beating drums. It was thought that the sounds must be different as night and day had different characters, with night being yin (negative energy) and day being yang (positive energy). Joseon-era Koreans believed that iron bells were yin, which symbolized night and sleep, while drums made of wood and leather were yang, which symbolized day and activities. So it was believed that injeong should be a bell sound for comfortable sleep in the night and paru should be a drum sound to wake people up in the morning with enough energy.

As the king had to wake up at paru, a water clock in Borugak Pavilion was installed near the king's bedroom or the rooms of the queen and concubines, to tell the time. In Gyeongbokgung Palace (the royal palace of the Joseon Dynasty), a water clock tower was located on the west side of Gangnyeongjeon Hall, the king's living quarters. During the reign of King Sejong, Jagyeongnu, an automatic water clock was invented and installed in Borugak Pavilion in the south side of Gyeonghoeru Pavilion. Special soldiers called jeonnugun (soldiers who announce the time) were stationed at every corner of the palaces and they would call out the time according to the water clock towers.

Since the chambers where the kings slept had ondol heating systems—which meant the heat came up through the floors—kings slept not on beds but on thin mattresses placed on the floor, with pillows and blankets as well. There were staff and facilities nearby to provide whatever he needed. Jimil-sanggung (palace matrons assigned to the king's bedroom) stayed just outside on standby overnight. Daejeon-chabi (palace custodians) who were in charge of kings' meals, the water he needed for washing, and the clothes he needed to put on at dawn, always stayed near the king's bedroom.

When the king woke up after paru, jimil-sanggung made bed, cooks at suragan (royal kitchen) prepared foods, and palace maids brought water for king's washing. Hwan-gwan (palace eunuch) also woke up to wait for king's orders.

Early morning was a time for the kings to get ready to display the dignity of the highest-ranking man in the country. During the night, the king slept like any other human being, but in the process of his early morning routine—having breakfast, getting dressed, and putting on a hat with assistance from servants—the king restored his dignity and authority again.

The bedroom for kings of the Joseon Dynasty was called jimil. Jimil referred to a space that was the most important and restricted in the entire palace, from which not one word spoken in it could leak outside. In such a space, the king stayed not with his queen but with maids of the court. The court maids who were assigned to work at jimil were called jimil-gungnyeo (court maids working at jimil).

Jeong Do-jeon was a high-ranking official who designed the structure of the Joseon Dynasty. Jeong established the spirit of the national foundation, as well as the policy line and national system. When Jeong Do-jeon named each building in Gyeongbokgung Palace by direction of King Taejo (Yi Seong-gye), he gave the name of Gangnyeongjeon Hall to the building in which the king's bedroom was located. Jeong thought gangnyeong (康寧, health and peace) was one of the Five Blessings (longevity, wealth, health, love of virtue, and peaceful death). Jeong said that when a king reached the state of hwanggeuk (royal perfection) by developing his mind and cultivating virtue, he would be endowed with the blessing of health and peace of body and mind, which could ultimately lead to the health and peace of the whole country and the universe. The reason why the king's living quarters in Gyeongbokgung Palace were named Gangnyeongjeon Hall had its roots in the concept of hwanggeuk.

Hwanggeuk is the same concept as taegeuk (also known as taiji, the great ultimate) used in the Eastern philosophy. In the Oriental philosophy, taegeuk refers to the basis that existed before the birth of all things in the universe. Taegeuk and hwanggeuk existed before the things in the universe could be classified as either yin or yang and right or left. As such, hwanggeuk was thought to be the state of the golden mean—the state that existed before the birth of human instincts such as the desire by the natural instincts.

Hwanggeuk is the state of moderation, so there exists no left or right or up and down in it. The state before the birth of different conflicts and divisions as well as before the proliferation of human desires was hwanggeuk and taegeuk. Jeong Do-jeon named the king's bedroom Gangnyeongjeon Hall to remind the king that he had to subdue his natural instincts for food, sex, and power by practicing hwanggeuk during the night. Jeong was showing the king that he could enjoy the Five Blessings only in that way. That message of course also implied a warning that the king would be punished by heaven if his life in the night were overwhelmed by the natural instincts for food, sex, and power.

Jeong Do-jeon also applied the concept of hwanggeuk to the location and space layout of Gangnyeongjeon Hall within Gyeongbokgung Palace: it was located at the center of the palace. Sajeongjeon Hall (the king's office) and Geunjeongjeon Hall (royal audience hall) were located in front of Gangnyeongjeon Hall. Huwon Garden (the backyard) was behind Gangnyeongjeon Hall, and Yeonsaengjeon Hall (the king's secondary quarters, annexed to Gangnyeongjeon Hall) and Gyeongseongjeon Hall (the king's secondary quarters) were located on the left and right sides of the Gangnyeongjeon Hall, respectively. Gyotaejeon Hall (the queen's living quarters) was built during the reign of King Sejong, which further consolidated Gangnyeongjeon Hall's central position in Gyeongbokgung Palace. As such, the king's living quarters were located at the very center of Gyeongbokgung Palace to signify the fact that the king's bedroom was hwanggeuk on earth. Just as hwanggeuk is the origin of the universe before its division into the positive and the negative and the left and right, the king's bedroom had to be undivided. That is why the king's bedroom could not be shared with any other person. He had to stay alone in his bedroom at the center of the royal palace and practice hwanggeuk there. Indeed, kings of the Joseon Dynasty did not share the bedroom with their queens.

Not only the location of the king's living quarters in the royal palace, but also the layout symbolized hwanggeuk. The king's sleeping chambers consisted of ondol rooms on the left and right sides and a daecheong (a wood-floored main hall) in the middle. The ondol rooms on the left and right were the actual bedrooms. Each bedroom looked like a sharp sign (#), a symbol deeply related to the concept of hwanggeuk. In the center of the sharp sign, there is a room surrounded by eight spaces. The central room symbolized hwanggeuk, while the surrounding eight spaces symbolized palgwae (eight trigrams). Of course, the room in which the king slept was the room at the center.

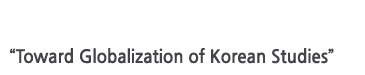

The structure of jimil, the king's bedroom in the Joseon Dynasty's royal palace, and the accompanying philosophy, were applied not only for Gangnyeongjeon Hall in Gyeongbokgung Palace but also to jimil in other palaces of the Joseon Dynasty, such as Daejojeon Hall in Changdeokgung Palace and Hamnyeongjeon Hall in Deoksugung Palace. As such, Joseon kings practiced hwanggeuk alone in their jimil, so that they could realize it in public and thus rule the country in a virtuous manner.

Hwanggeuk is the same concept as taegeuk (also known as taiji, the great ultimate) used in the Eastern philosophy. In the Oriental philosophy, taegeuk refers to the basis that existed before the birth of all things in the universe. Taegeuk and hwanggeuk existed before the things in the universe could be classified as either yin or yang and right or left. As such, hwanggeuk was thought to be the state of the golden mean—the state that existed before the birth of human instincts such as the desire by the natural instincts.

Hwanggeuk is the state of moderation, so there exists no left or right or up and down in it. The state before the birth of different conflicts and divisions as well as before the proliferation of human desires was hwanggeuk and taegeuk. Jeong Do-jeon named the king's bedroom Gangnyeongjeon Hall to remind the king that he had to subdue his natural instincts for food, sex, and power by practicing hwanggeuk during the night. Jeong was showing the king that he could enjoy the Five Blessings only in that way. That message of course also implied a warning that the king would be punished by heaven if his life in the night were overwhelmed by the natural instincts for food, sex, and power.

Jeong Do-jeon also applied the concept of hwanggeuk to the location and space layout of Gangnyeongjeon Hall within Gyeongbokgung Palace: it was located at the center of the palace. Sajeongjeon Hall (the king's office) and Geunjeongjeon Hall (royal audience hall) were located in front of Gangnyeongjeon Hall. Huwon Garden (the backyard) was behind Gangnyeongjeon Hall, and Yeonsaengjeon Hall (the king's secondary quarters, annexed to Gangnyeongjeon Hall) and Gyeongseongjeon Hall (the king's secondary quarters) were located on the left and right sides of the Gangnyeongjeon Hall, respectively. Gyotaejeon Hall (the queen's living quarters) was built during the reign of King Sejong, which further consolidated Gangnyeongjeon Hall's central position in Gyeongbokgung Palace. As such, the king's living quarters were located at the very center of Gyeongbokgung Palace to signify the fact that the king's bedroom was hwanggeuk on earth. Just as hwanggeuk is the origin of the universe before its division into the positive and the negative and the left and right, the king's bedroom had to be undivided. That is why the king's bedroom could not be shared with any other person. He had to stay alone in his bedroom at the center of the royal palace and practice hwanggeuk there. Indeed, kings of the Joseon Dynasty did not share the bedroom with their queens.

Not only the location of the king's living quarters in the royal palace, but also the layout symbolized hwanggeuk. The king's sleeping chambers consisted of ondol rooms on the left and right sides and a daecheong (a wood-floored main hall) in the middle. The ondol rooms on the left and right were the actual bedrooms. Each bedroom looked like a sharp sign (#), a symbol deeply related to the concept of hwanggeuk. In the center of the sharp sign, there is a room surrounded by eight spaces. The central room symbolized hwanggeuk, while the surrounding eight spaces symbolized palgwae (eight trigrams). Of course, the room in which the king slept was the room at the center.

The structure of jimil, the king's bedroom in the Joseon Dynasty's royal palace, and the accompanying philosophy, were applied not only for Gangnyeongjeon Hall in Gyeongbokgung Palace but also to jimil in other palaces of the Joseon Dynasty, such as Daejojeon Hall in Changdeokgung Palace and Hamnyeongjeon Hall in Deoksugung Palace. As such, Joseon kings practiced hwanggeuk alone in their jimil, so that they could realize it in public and thus rule the country in a virtuous manner.

Infokorea 2016

Infokorea is Korea introduced a magazine designed for readers with an interest in Korea and other foreign producers textbooks and teachers. Infokorea is the author of textbooks or foreign editors and reference to textbooks, Korea provides the latest information that teachers can use in teaching resources. Infokorea also provides cultural, social and historical topics featured in Korea. The theme of the 2016 issue was overview of Korea's palaces.

Infokorea is Korea introduced a magazine designed for readers with an interest in Korea and other foreign producers textbooks and teachers. Infokorea is the author of textbooks or foreign editors and reference to textbooks, Korea provides the latest information that teachers can use in teaching resources. Infokorea also provides cultural, social and historical topics featured in Korea. The theme of the 2016 issue was overview of Korea's palaces.