Column

Demonstrations and Coronavirus,

Chilean Students' On-screen Challenges

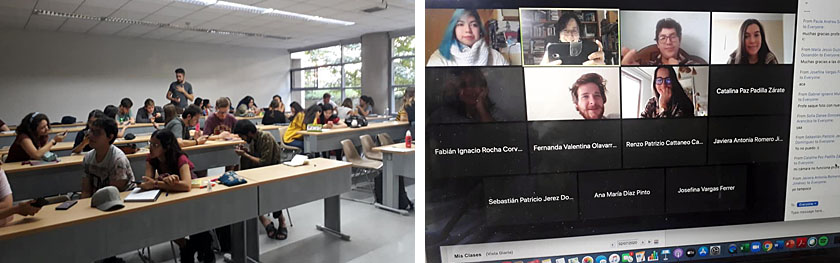

On October 18, 2019, middle and high school students held a demonstration at Baquedano Station, which runs through the center of Santiago, the capital of Chile, to protest the KRW 50 hike in subway fares. The protest was reported by the Korean media. On the surface, the subway fare hike seemed to have prompted the demonstration, but underneath the protests that were continuing into the last days of 2020 was the deep-seated anger against the long-standing class society. At least since 2004 when I started working in Chile, the academic schedule of the Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile had never been disrupted. Still, even the university has had difficulties running classes since the protests began. The ticket gates at the subway station in front of the San Joaquin campus of the Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile were destroyed by protesters and closed for months. Eventually, the semester came to an end with the submission of assignments and examinations through the online class platform. Since the demonstrations had been expected to go on for a while, the university prepared for online non-face-to-face classes in order to prevent disruption of the academic schedule.

The new semester began in March 2020. Exchanging greetings with the students, I told them that the class would be held in a non-face-to-face way if the protests affect transportation or force the closure of the university. Since the second week of the semester, however, I have had to hold non-face-to-face classes due to the COVID-19 pandemic, not the protests, for the rest of the semester.

Online non-face-to-face classes have begun. In Chile where the gap between the rich and the poor is wide (the worst in OECD), many students could not show their faces on the screen due to the lack of Internet connection. It was difficult to ask only the students who lived in a relatively better Internet environment to show their faces. There were no fellow professors who took pains with virtual screens, microphones, and ring illumination. All we could manage was to do our best in the given environment. Some students took classes only on their cell phones throughout the semester, whereas others relied on laptops lent by colleges. The situation worsened in the middle of March when the entire city of Santiago was placed in a lockdown as students were not able to go to school where they can get laptops. Employees of Internet companies were working from home, which interfered with their maintenance work, and Internet speed slowed down further as the number of users kept spiking. When it is raining on class days, I kept worrying that the electricity or Internet connection might get cut off.

Students actively participated in classes despite the difficult situation. In the first-semester class on Korean history and culture, I gradually increased the number of books available online at the university library. I had to use as many online class materials as possible. In case of an emergency, I created SNS communication channels with students. In order to encourage the participation of students who were tired of the demonstrations and COVID-19, I opened the screen 10 minutes before the class and played various kinds of Korean music ranging from K-pop to pansori. An increasing number of students began logging in to the class before the starting time in order to enjoy the music.

In the Korean history and culture class, students are divided into groups each of which makes a presentation. At the end of the semester, students hold a "post-unification" simulation debate under the assumption that the Korean Peninsula has been unified. The students barely got to know each other in the first week of class and had difficulty meeting each other because of the lockdown in the city. The students, however, gave wonderful presentations. They even prepared a video clip in case they had difficulty accessing the Internet on the day of the presentation. Miraculously, all the students were connected to the last class of the semester, where there was a post-unification simulation debate. It may be hard to understand in Korea, but such a thing is never easy in Chile, whose infrastructure is not as good as that in Korea. The students were divided into South Korea, North Korea, Russia, United States, Japan, and China similar to the six-party talks on the North Korean nuclear issue. The students set the time for each group's presentation and engaged in a good debate. All the students praised each other and patted themselves on the back.

At the Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, there have been many activities related to Korean studies. Since the opening of Korean studies classes in 2006, there have been 11 contests for Korean studies papers for undergraduate students, from 2007 to 2016 and in 2018. There have been 10 international academic conferences on Korean studies from 2008 to 2016 and in 2018. From the 4th International Korean Studies Conference in 2011, five to seven students who had taken Korean history and culture classes were selected to form a Junior Panel that participated in the post-unification simulation debate. The debates had a different topic each year. There are two volumes of the collection of winning works of the Korean studies paper contest, which were compiled every four years. The collection of the papers presented at the academic conferences was published every two years, and there are now five volumes.

Despite the repeated lockdowns caused by COVID-19, protests are still persisting. In October this year, a referendum on the constitutional amendment was passed, but citizens insist that they will not stop protesting until a new constitution is enacted. The publication of the sixth volume of the International Academic Conference on Korean Studies had to be postponed as well. All the classes in the second semester of 2020 were held in non-face-to-face formats, and that will remain the case at least until the first semester of 2021. All universities in Chile will see all the students become the first generation to spend their last year of high school entirely online and become college freshmen online as well.

The demonstrations and the COVID-19 pandemic have caused changes in activities related to Korean studies in Chile. The cumulative number of confirmed cases compared to the population is so large (as of December 19, 2020, 583,354 people out of a population of about 19 million were infected) that it is not rare to hear students who had taken Korean studies classes or their families catching the disease. The number of students suspending their studies or leaving the university for good in the middle of the semester is also increasing because the more than a year of protests and the pandemic have worsened the economic situation. There is a possibility that interest in Korean studies may decrease in Chile and many other Latin American countries. Nevertheless, 50 students took the class on Korean history and culture and the class on cross-cultural studies of Korea and Latin America in the first semester of 2020. Everyone did his/her best in the given environment. The difficult situation is expected to continue for quite a long time even after the end of the COVID-19 crisis. I still hope that a Korean studies program suitable for the situation will be developed, and that interest in Korean studies will continue to be high in Chile.

The new semester began in March 2020. Exchanging greetings with the students, I told them that the class would be held in a non-face-to-face way if the protests affect transportation or force the closure of the university. Since the second week of the semester, however, I have had to hold non-face-to-face classes due to the COVID-19 pandemic, not the protests, for the rest of the semester.

Online non-face-to-face classes have begun. In Chile where the gap between the rich and the poor is wide (the worst in OECD), many students could not show their faces on the screen due to the lack of Internet connection. It was difficult to ask only the students who lived in a relatively better Internet environment to show their faces. There were no fellow professors who took pains with virtual screens, microphones, and ring illumination. All we could manage was to do our best in the given environment. Some students took classes only on their cell phones throughout the semester, whereas others relied on laptops lent by colleges. The situation worsened in the middle of March when the entire city of Santiago was placed in a lockdown as students were not able to go to school where they can get laptops. Employees of Internet companies were working from home, which interfered with their maintenance work, and Internet speed slowed down further as the number of users kept spiking. When it is raining on class days, I kept worrying that the electricity or Internet connection might get cut off.

Students actively participated in classes despite the difficult situation. In the first-semester class on Korean history and culture, I gradually increased the number of books available online at the university library. I had to use as many online class materials as possible. In case of an emergency, I created SNS communication channels with students. In order to encourage the participation of students who were tired of the demonstrations and COVID-19, I opened the screen 10 minutes before the class and played various kinds of Korean music ranging from K-pop to pansori. An increasing number of students began logging in to the class before the starting time in order to enjoy the music.

In the Korean history and culture class, students are divided into groups each of which makes a presentation. At the end of the semester, students hold a "post-unification" simulation debate under the assumption that the Korean Peninsula has been unified. The students barely got to know each other in the first week of class and had difficulty meeting each other because of the lockdown in the city. The students, however, gave wonderful presentations. They even prepared a video clip in case they had difficulty accessing the Internet on the day of the presentation. Miraculously, all the students were connected to the last class of the semester, where there was a post-unification simulation debate. It may be hard to understand in Korea, but such a thing is never easy in Chile, whose infrastructure is not as good as that in Korea. The students were divided into South Korea, North Korea, Russia, United States, Japan, and China similar to the six-party talks on the North Korean nuclear issue. The students set the time for each group's presentation and engaged in a good debate. All the students praised each other and patted themselves on the back.

At the Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, there have been many activities related to Korean studies. Since the opening of Korean studies classes in 2006, there have been 11 contests for Korean studies papers for undergraduate students, from 2007 to 2016 and in 2018. There have been 10 international academic conferences on Korean studies from 2008 to 2016 and in 2018. From the 4th International Korean Studies Conference in 2011, five to seven students who had taken Korean history and culture classes were selected to form a Junior Panel that participated in the post-unification simulation debate. The debates had a different topic each year. There are two volumes of the collection of winning works of the Korean studies paper contest, which were compiled every four years. The collection of the papers presented at the academic conferences was published every two years, and there are now five volumes.

Despite the repeated lockdowns caused by COVID-19, protests are still persisting. In October this year, a referendum on the constitutional amendment was passed, but citizens insist that they will not stop protesting until a new constitution is enacted. The publication of the sixth volume of the International Academic Conference on Korean Studies had to be postponed as well. All the classes in the second semester of 2020 were held in non-face-to-face formats, and that will remain the case at least until the first semester of 2021. All universities in Chile will see all the students become the first generation to spend their last year of high school entirely online and become college freshmen online as well.

The demonstrations and the COVID-19 pandemic have caused changes in activities related to Korean studies in Chile. The cumulative number of confirmed cases compared to the population is so large (as of December 19, 2020, 583,354 people out of a population of about 19 million were infected) that it is not rare to hear students who had taken Korean studies classes or their families catching the disease. The number of students suspending their studies or leaving the university for good in the middle of the semester is also increasing because the more than a year of protests and the pandemic have worsened the economic situation. There is a possibility that interest in Korean studies may decrease in Chile and many other Latin American countries. Nevertheless, 50 students took the class on Korean history and culture and the class on cross-cultural studies of Korea and Latin America in the first semester of 2020. Everyone did his/her best in the given environment. The difficult situation is expected to continue for quite a long time even after the end of the COVID-19 crisis. I still hope that a Korean studies program suitable for the situation will be developed, and that interest in Korean studies will continue to be high in Chile.