Culture Focus

An Overview of Korea's Palaces - 3

Palaces Backed by Mountains

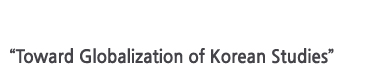

Hanyang was surrounded by four mountains: Mt. Bugaksan to the north, Mt. Inwangsan to the west, Mt. Naksan to the east, and Mt. Mongmyeoksan to the south. At 342 meters, Mt. Bugaksan was the tallest. When it came to an imposing presence, however, Mt. Inwangsan outshined Mt. Bugaksan with its towering rocks. Compared with the impressive Mt. Inwangsan, Mt. Naksan is not very tall and had a less graceful shape. Mt. Mongmyeoksan, on the other hand, had a magnificently straight posture and stood right at the southern end of the capital, earning it a special place in the people's hearts. Because of its location, Mt. Mongmyeoksan came to be called Mt. Namsan. ("Nam" means "south" in Korean.)

In addition to the four mountains, Hanyang had Eungbong Peak in the due north position, directly opposite Mt. Mongmyeoksan. Because of its geographical position, feng shui experts maintained that Eungbong Peak deserved the honor of being the city's main mountain, under which the main palace should have been built.

Of the five grand palaces of the Joseon Dynasty, the first four were built at the feet of mountains: Gyeongbokgung Palace had Mt. Bugaksan in the background, and Eungbong Peak overlooked Changdeokgung Palace and Changgyeonggung Palace. The concept of feng shui heavily influenced these choices of location: Mountains could shut out the wind, and palace residents could use the water that flowed down from them. Such ideas also influenced court life.

Hanyang was surrounded by eighteen-kilometer-long ramparts, which were heaped up along its ridges. Ramparts had two purposes: defending the capital from enemy attack, and controlling the flow of people in and out of the city gates. The city had eight gates, one in each of the four great directions and four others in between, which the king's officials opened every morning and closed in the evening. The number eight symbolized the king's authority over the whole land. But considering the mountainous terrain and the presence of so many ridges, it was virtually impossible to build the gates precisely at the designated points of due north, due east, due west, and due south. In some cases, people couldn't use a gate that was built on a ridge. For this reason, although the city's eastern, western, and southern gates were opened to the public, the northern gate almost always remained shut.

The four palaces of Hanyang were connected to the main road either directly or indirectly. Gyeongbokgung Palace was located at the end of a wide street that extended north from the main road, beginning at Jongnu. This wide street was called Yukjodaero, and government buildings stood on both sides. Changdeokgung Palace was at the end of another road that extended north from the main road, turning off at a point some two kilometers east of Jongnu. This street was called Donhwamun-ro and was named after the main gate of Changdeokgung Palace. At the main gate of Changgyeonggung Palace was a narrow street that ran from north to south; the southern end joined the western part of the main road. The main gate of Gyeonghuigung Palace was linked with the part of the main road.

The jangnang started at Jongnu and extended to Donhwamun Gate at Changdeokgung Palace to the east; to Gwanghwamun Gate at Gyeongbokgung Palace to the west; and to Namdaemun Gate to the south. With the establishment of the jangnang, Unjong-ga was equipped with an array of buildings, similar in form and height, on both sides of the street.

Gwanghwamun Gate, the main entrance to Gyeongbokgung Palace, faced Yukjodaero, which literally means "six-ministry street." On that street, arranged on both sides, were the six top government ministries. Additional buildings included the Hanseong Metropolitan Office or "Hanseongbu," the body in charge of the administrative affairs of Hanyang; and the Office of the Censor-General or "Saganwon," who was responsible for criticizing the king's policies and checking his power. In the early period after the founding of the dynasty, the State Council (Uijeongbu) and the Three Armies Command (Samgunbu) sat facing each other on either side of the street. The former was in charge of comprehensive state affairs across the nation and the latter dealt with military affairs. During the reign of the third monarch, King Taejong, the six government ministries virtually took charge of state affairs after the Three Armies Command was abolished and the State Council remained as a nominal government agency.

Yukjodaero was approximately 500 meters long and more than 50 meters wide. On either side was an array of jangnang; officials could enter the nation's top government buildings through the high gates built at several points along the jangnang. The street was the symbol of Hanyang, as it was here that the king issued orders and proclaimed them across the nation. Gwanghwamun Gate, at the end of Yukjodaero, was another major symbol as the entrance to Gyeongbokgung Palace, the residence of the king. The colorful royal parade started and ended at the gate. The envoys sent by the Chinese emperor also passed the gate via Yukjodaero.

Yukjodaero had its heyday during the golden age of Gyeongbokgung Palace in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. After Gyeongbokgung Palace burned down during the Japanese invasion in 1592, the site lay deserted for some 250 years; as a result, Yukjodaero lost its visitors and the once-dignified government buildings could not fulfill their functions properly. At this point, Donhwamun-ro (the street in front of Donhwamun Gate) took on the former role of Yukjodaero.

In addition to the four mountains, Hanyang had Eungbong Peak in the due north position, directly opposite Mt. Mongmyeoksan. Because of its geographical position, feng shui experts maintained that Eungbong Peak deserved the honor of being the city's main mountain, under which the main palace should have been built.

Of the five grand palaces of the Joseon Dynasty, the first four were built at the feet of mountains: Gyeongbokgung Palace had Mt. Bugaksan in the background, and Eungbong Peak overlooked Changdeokgung Palace and Changgyeonggung Palace. The concept of feng shui heavily influenced these choices of location: Mountains could shut out the wind, and palace residents could use the water that flowed down from them. Such ideas also influenced court life.

Gyeongungung Palace: A New Perspective

The construction of Gyeongungung Palace in the early twentieth century was an exception, situated at the center of Hanyang with no mountain in the background. Why was this hitherto cherished tradition neglected? The reason had to do with the political situation of the Joseon Kingdom in the early twentieth century. Faced with a complex political reality and the need for decisive action to counter the bold aggression of Japan, King Gojong moved first to the Russian Consulate and then to Gyeongungung Palace, where he proclaimed the establishment of the Great Han Empire to show its full independence to the world. Given the circumstances, Gyeongungung Palace was built on the site where it could command the greatest political power and guarantee smooth traffic. Gyeongungung Palace stands at the heart of the capital, a place where many streets converge. Its geographical and political advantages led the emperor to disregard the time-honored principles of geomancy.The Main Roads and the Palace Gates

When Hanyang was established as the new capital, city planners envisioned not one main road but several. They intended to build a road that would bisect the capital from east to west, and another that would stretch south from the city center. It was not easy to conceive of a pattern of intersecting straight lines in a city surrounded by mountains. The main roads of Hanyang therefore took a curved shape. Other than a few main roads, most of Hanyang's roads formed spontaneously along the waterways.Hanyang was surrounded by eighteen-kilometer-long ramparts, which were heaped up along its ridges. Ramparts had two purposes: defending the capital from enemy attack, and controlling the flow of people in and out of the city gates. The city had eight gates, one in each of the four great directions and four others in between, which the king's officials opened every morning and closed in the evening. The number eight symbolized the king's authority over the whole land. But considering the mountainous terrain and the presence of so many ridges, it was virtually impossible to build the gates precisely at the designated points of due north, due east, due west, and due south. In some cases, people couldn't use a gate that was built on a ridge. For this reason, although the city's eastern, western, and southern gates were opened to the public, the northern gate almost always remained shut.

The Main Roads and the Palaces

The city's main road stretched from east to west. Along that road, a large bell hung on a tall building, tolling every hour to herald the time to the people on the street. The building was called Jongnu, and the main road was called Unjong-ga (literally meaning "a road where people flock together like clouds"). Later, the name changed to Jongno (literally, "bell street"). On the main road surrounding the Jongnu tower were shops that sold daily necessities. The people of Hanyang would go to Unjong-ga to buy the food and clothes they needed, and sometimes just for a stroll.The four palaces of Hanyang were connected to the main road either directly or indirectly. Gyeongbokgung Palace was located at the end of a wide street that extended north from the main road, beginning at Jongnu. This wide street was called Yukjodaero, and government buildings stood on both sides. Changdeokgung Palace was at the end of another road that extended north from the main road, turning off at a point some two kilometers east of Jongnu. This street was called Donhwamun-ro and was named after the main gate of Changdeokgung Palace. At the main gate of Changgyeonggung Palace was a narrow street that ran from north to south; the southern end joined the western part of the main road. The main gate of Gyeonghuigung Palace was linked with the part of the main road.

Yukjodaero and Jangnang

King Taejong refurbished Hanyang's central street on a grand scale and built long, high corridors called jangnang (長廊) alongside it. The main purposes of the jangnang were road maintenance and the formation of a central shopping district at the heart of the capital. Jangnang had another utility: veiling the lives of the commoners from the eyes of foreign envoys.The jangnang started at Jongnu and extended to Donhwamun Gate at Changdeokgung Palace to the east; to Gwanghwamun Gate at Gyeongbokgung Palace to the west; and to Namdaemun Gate to the south. With the establishment of the jangnang, Unjong-ga was equipped with an array of buildings, similar in form and height, on both sides of the street.

Gwanghwamun Gate, the main entrance to Gyeongbokgung Palace, faced Yukjodaero, which literally means "six-ministry street." On that street, arranged on both sides, were the six top government ministries. Additional buildings included the Hanseong Metropolitan Office or "Hanseongbu," the body in charge of the administrative affairs of Hanyang; and the Office of the Censor-General or "Saganwon," who was responsible for criticizing the king's policies and checking his power. In the early period after the founding of the dynasty, the State Council (Uijeongbu) and the Three Armies Command (Samgunbu) sat facing each other on either side of the street. The former was in charge of comprehensive state affairs across the nation and the latter dealt with military affairs. During the reign of the third monarch, King Taejong, the six government ministries virtually took charge of state affairs after the Three Armies Command was abolished and the State Council remained as a nominal government agency.

Yukjodaero was approximately 500 meters long and more than 50 meters wide. On either side was an array of jangnang; officials could enter the nation's top government buildings through the high gates built at several points along the jangnang. The street was the symbol of Hanyang, as it was here that the king issued orders and proclaimed them across the nation. Gwanghwamun Gate, at the end of Yukjodaero, was another major symbol as the entrance to Gyeongbokgung Palace, the residence of the king. The colorful royal parade started and ended at the gate. The envoys sent by the Chinese emperor also passed the gate via Yukjodaero.

Yukjodaero had its heyday during the golden age of Gyeongbokgung Palace in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. After Gyeongbokgung Palace burned down during the Japanese invasion in 1592, the site lay deserted for some 250 years; as a result, Yukjodaero lost its visitors and the once-dignified government buildings could not fulfill their functions properly. At this point, Donhwamun-ro (the street in front of Donhwamun Gate) took on the former role of Yukjodaero.

Parades in the Narrow Street: Donhwamun-ro

Donhwamun-ro extended some 700 meters from the main gate of Changdeokgung Palace to Unjong-ga. Donhwamun-ro did not have to be as wide as Yukjodaero considering the original purpose of Changdeokgung Palace as the king's temporary residence. However, with Gyeongbokgung Palace in need of reconstruction, the king had to use Changdeokgung Palace both as his residence and as the venue for all the ceremonies and festivities formerly held on Yukjodaero. Until Gyeongbokgung Palace was renovated in 1868, most royal parades took place on Donhwamun-ro.The street's narrower width and the absence of government offices meant the ceremonies had to be performed less brilliantly and on a smaller scale. Gigantic parades were impossible, and decorations on the side streets had to be comparatively simple. Nevertheless, parades were grand enough to pack the streets and onlookers had a chance to see the king from up close when he passed by.

Sometimes people would block the parades and express their grievances directly to the king by playing noisy gongs in a tradition called gyeokjaeng. In gyeokjaeng, people who had been wrongfully accused or injured could beat drums or gongs outside the palace gate and tell their stories to those in charge. This tradition moved to Donhwamun-ro when royal parades were under way.

Changgyeonggung Palace: A Place for Royal Funeral Rites

Built as a residence for queen dowagers, Changgyeonggung Palace was later used for many different purposes. Next to Changdeokgung Palace and separated from it by a wall, Changgyeonggung Palace also functioned as a royal mansion that complemented Changdeokgung Palace. Queen dowagers and royal concubines resided at Changgyeonggung Palace. A palace for the crown prince was also established there. Furthermore, Changgyeonggung Palace served as a funeral home for deceased royal family members.When a king, a queen, a queen dowager, or a crown prince passed away, the family would put the body inside the palace for five months to pay respects. Pyeonjeon, the king's office in the palace, was used for this purpose. After five months, the deceased family member was buried in the royal tomb. The memorial tablet was kept at a temporary shrine set up within the palace for a memorial service that lasted twenty-five months.

After the seventeenth century, deceased royal family members were carried out of the palace through Honghwamun Gate, the main gate of Changgyeonggung Palace, on splendidly decorated funeral palanquins. From Honghwamun Gate, the palanquins moved along Unjong-ga and then, in most cases, through Heunginjimun Gate, the city's east gate. During the Joseon Dynasty, royal tombs were scattered around the capital, but were mostly clustered in its eastern suburbs. Honghwamun Gate became the official entrance for funeral processions. It is believed that the royal family used Changgyeonggung Palace for this purpose in order to avoid bringing such sorrow into Changdeokggung Palace. Honghwamun Gate was tall and wide in proportion to Changgyeonggung Palace because it had to accommodate funeral parades.

Infokorea 2016

Infokorea is Korea introduced a magazine designed for readers with an interest in Korea and other foreign producers textbooks and teachers. Infokorea is the author of textbooks or foreign editors and reference to textbooks, Korea provides the latest information that teachers can use in teaching resources. Infokorea also provides cultural, social and historical topics featured in Korea. The theme of the 2016 issue was overview of Korea's palaces.

Infokorea is Korea introduced a magazine designed for readers with an interest in Korea and other foreign producers textbooks and teachers. Infokorea is the author of textbooks or foreign editors and reference to textbooks, Korea provides the latest information that teachers can use in teaching resources. Infokorea also provides cultural, social and historical topics featured in Korea. The theme of the 2016 issue was overview of Korea's palaces.